1945 and 2015 at Trinity Site, where the atomic bomb was born

By Martin Kufus

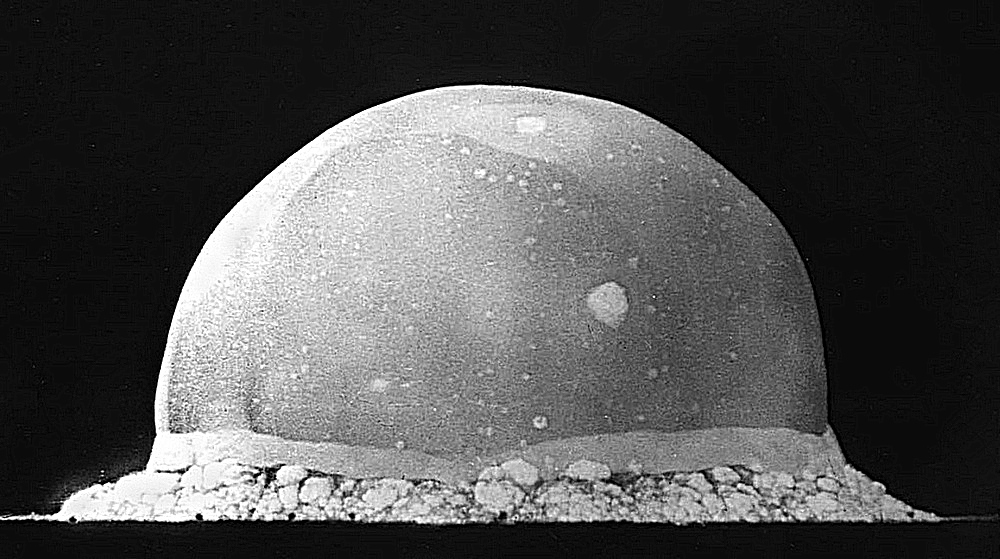

Minutes before dawn on July 16, 1945, a blinding man-made sun rose terrifyingly 27 miles from this small town south of Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA.

Locals for months had known something unusual was taking place out on vast ranchlands the Army had appropriated beyond the rough hills ascending to Jornada del Muerto: south–central New Mexico’s “journey of the dead man.”

Exactly what was going on southeast of San Antonio—that was top secret. There was a war on.

“The day it happened,” the cashier at San Antonio’s Owl Bar and Café said in 2015, “my great-grandmother thought it was the end of the world. She put the children under the bed!”

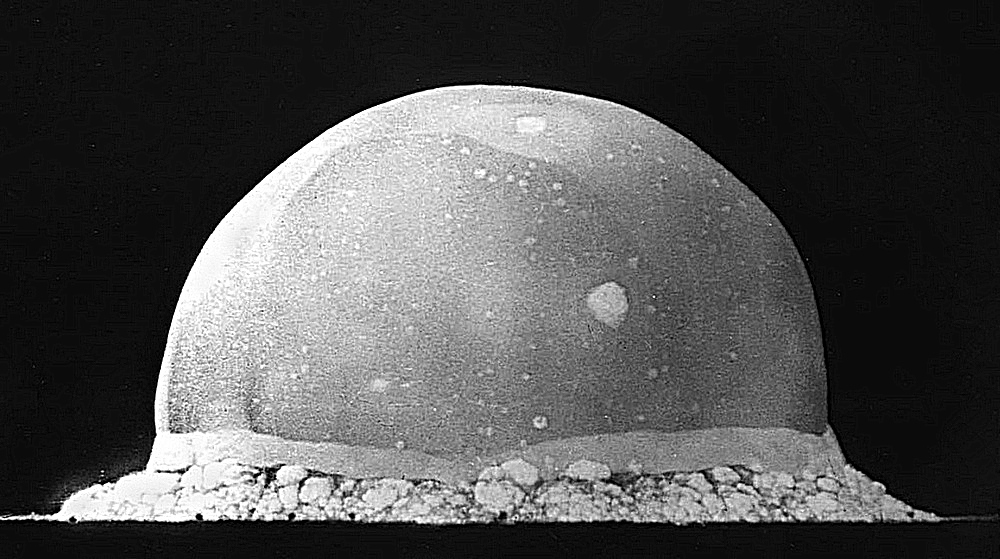

The world did not end at 5:29 a.m., on July 16, 1945. But, it forever was changed by events in the American Southwest. The atomic age had arrived at a place called Trinity Site. Scientists calculated the world’s first atomic bomb exploded with the equivalence of 20 kilotons—40 million pounds—of TNT.

“The heat was like opening up an oven door, even at 10 miles,” a military policeman at the base camp remarked, according to an Army public-affairs booklet, Trinity Site—July 16, 1945.

The A-bomb project’s director, Army Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves, an engineer and blunt-spoken bear of a man, had ordered up a cover story.

“Although no information on the test was released until after the atomic bomb was used as a weapon against Japan, people in New Mexico knew something had happened,” the booklet says. “The shock wave broke windows 120 miles away and was felt by many at least 160 miles away. Army officials simply stated that a munitions storage area had accidentally exploded at the Alamogordo Bombing Range.”

Green-chile cheeseburgers

San Antonio had few businesses in 1945. One was the Owl Bar.

Local son Frank Chavez opened it in ’45 after returning from World War II duty in the Navy. He and his wife Dee started frying hamburgers (according to the Owl’s history) for new customers who said they were “prospectors.” One of them almost certainly was a skinny man with piercing eyes under a pork-pie hat.

Born in New York City to affluent German-Jewish parents, J. Robert Oppenheimer had been educated in physics on both sides of the Atlantic. However, he had fallen in love with New Mexico as a teenager riding horses and camping on a guest ranch (according to the 2005 book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer). Now, the charismatic Oppenheimer was the intellectual nucleus of a national crash program that had been undertaken to create a megabomb before Nazi Germany and use it on the Third Reich.

Whether “Oppie”—as his staff, fellow academics at Berkeley and Stanford, and friends knew him—actually kicked back in the Chavez’s Owl to chain-smoke cigarettes, sip soda or beer (instead of his favored martinis), and eat cheeseburgers topped with green chile or not perhaps is lost to history.

These “prospectors” and military officers never let slip what was coming.

It arrived at the base camp southeast of San Antonio as the bulky, plutonium-cored device built at the super-secret laboratory at Los Alamos, some 160 miles to the north. The 5,000-pound “gadget” would perch 100 feet above Trinity sands on a steel tower to approximate a wartime aerial burst.

‘Manhattan Project’

A 1939 letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed by expatriate German physicist Albert Einstein had warned of the theoretical possibility of “a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium” in a bomb. Einstein had left Germany in 1932 just before the Jew-hating Adolf Hitler became chancellor. The world-famous physicist hinted strongly at Germany’s interest in this field.

The Manhattan Project began in June 1942. By 1945, however, the winds of war had shifted. A vengeful Red Army roared westward into Germany from the invasion-ravaged USSR.

American-led allied forces pushed eastward from formerly occupied France. (Germany’s A-bomb program, it would be discovered, never had gotten very far.) But, imperial Japan still fought.

The 82-day Allied amphibious invasion of nearby Okinawa produced very large numbers of casualties among invaders, defenders, and civilians. An invasion of the Japanese homeland would have been far worse.

After Trinity Site’s success, the Army with the Navy’s help hurriedly transported two atomic weapons and technical staff across the Pacific Ocean. Japanese cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki were on early-August target lists for the uranium-gun-type “Little Boy” and plutonium-implosion “Fat Man” bombs, respectively, carried by Army B-29 bombers flying from an island base. President Harry Truman, historians speculate, also calculated the A-bombs would discourage Communist dictator Josef Stalin from any Soviet move on Japan.

In terms of immense costs, cutting-edge science and engineering, nationwide research and industrial support, and national prestige, the Manhattan Project has been compared to the Apollo lunar program of two decades later. (And, to that end, 67 captured Nazi V-2 ballistic missiles were modified and test-launched high over New Mexico’s White Sands region beginning in May 1946.)

‘Open house’ at Trinity

It was minutes before noon on April 4, 2015.

The Owl Café and Saloon was busy; a line of customers almost was out the front doors. Across and down San Antonio’s main street, the Buckhorn Tavern—the Owl’s nationally known rival (via TV celebrity chef Bobby Flay in 2009) for Hatch-green-chile-cheeseburger supremacy—was busy.

A rare “open house” at the Trinity Site on the northern end of the 3,200-square-mile White Sands Missile Range (WSMR) would draw more than 5,500 visitors—an event record. Among them was a Japanese TV crew.

WSMR’s Stallion Gate is about a 17-mile drive east of San Antonio. The gate would be opened to the public at 8 a.m., for only six hours. At 6:45 a.m., there were 20 vehicles outside the gate. At opening, the line stretched a mile or more. By 11 a.m., the line of vehicles was about 4 miles long.

A dozen or more people with handmade signs stood or sat in camping chairs a respectful distance from Stallion Gate. Members of the “Tularosa Basin Downwinders” wanted tourists to stop and talk about their unresolved claim the 1945 fallout harmed generations of family and friends.

‘Jumbo’ and Trinitite

After clearing the gate’s armed guards, “atomic tourists” drove past a WSMR missile-launch-observation compound—no stopping or photos allowed—and south–southeast on a 17-mile range road to a large parking area and series of chain-linked fences. Anybody expecting a museum or theme park would be disappointed: Trinity is a special place where the more knowledge a visitor brings, the greater the experience.

In fact, the largest object there—beside and inside of which many atomic tourists have posed for snapshots—actually did nothing in 1945.

Cylindrical “Jumbo,” originally a 214-ton steel container measuring 25 feet in length and 10 feet in diameter, was built to hold an A-bomb misfire. Los Alamos scientists initially feared the conventional explosives encasing the plutonium core might not create and sustain a nuclear chain reaction; that the explosion would scatter the precious and dangerous plutonium (nowadays, we’d call it a “dirty bomb”) and so Jumbo would contain it all or be vaporized in a successful atomic blast. However, the scientists became more confident and Jumbo was parked 800 yards away. Now, it sits near the entrance to the short walk to ground zero at Trinity Site.

In that fenced-in, circular area stands the stone obelisk with bronze plaques; almost all atomic tourists pose beside it for photos. A few feet away is—amazingly—a remnant of the original concrete-and-metal footing of the 100-foot tower.

On a trailer a short distance away sits the almost 5,000-pound, empty casing of a next-generation “Fat Man” built in the first years of the Cold War. Another important place is about 3 miles away by shuttle buses: the vacated McDonald Ranch House that was converted in 1945 to an “assembly point” for the A-bomb’s plutonium-and-explosive core.

Many of the atomic tourists strolling across ground zero April 4 did so with heads bowed; maybe, pondering the enormity of this grim history—but, more likely, looking underfoot for a little sparkle of green: the atomic-age substance Trinitite, the melted sand (most of which was hauled away decades ago). This fascination is shared. In 2004, Los Alamos scientists reinvestigated Trinitite’s formation, according to the Trinity Site—July 16, 1945 booklet. From that, they calculated the 1945 fireball’s temperature at 14,710 degrees Fahrenheit.

Trinity’s somewhat-elevated radiation levels, meanwhile, slowly drop to “background” normal. 2015’s remaining gathering of atomic tourists was held Oct. 3.

Photo captions:

1) At 16 milliseconds the world’s first atomic blast rises hundreds of meters above Trinity Site—as filmed by super high-speed movie cameras at an astonishing range of 800 yards, or less than one-half mile. (Photo: US Army, 1945)

2) April 4, 2015: A monument marks “ground zero” at Tinity Site, during a public event. Several feet away from the monument a rough piece of concrete and some metal stick out of the soil—the remains of the 100-foot steel tower. The “Fat Man” bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, in August 1945 was the prototype for this MK III bomb (circa 1947–50) whose empty casing is displayed on a trailer.

3) Most Trinity Site visitors overlook what is left of the “West 800 Instrumentation Shelter,” the reinforced bunker that sheltered cameras and radiation-measuring instruments. The cameras occupied lead-lined boxes (shielding film against ruinous gamma rays) on the back side of the bunker and received imagery via a series of mirrors. The boxes had been attached to sleds to be pulled safely out of the high radioactivity with steel cables.

4) Residue from the atomic test still exists at Trinity Site. 1945’s nuclear fireball melted sand on the ground but also sucked it high into the superheated air and it fell to earth as drops of colored liquid. It coalesced into a new substance: “Trinitite.” Decades ago, Atomic Energy Commission crews filled in much of the blast’s depression and hauled away most, but not all, of the Trinitite. It now is illegal to remove any from the national landmark (where radioactivity levels are almost normal).

4) Residue from the atomic test still exists at Trinity Site. 1945’s nuclear fireball melted sand on the ground but also sucked it high into the superheated air and it fell to earth as drops of colored liquid. It coalesced into a new substance: “Trinitite.” Decades ago, Atomic Energy Commission crews filled in much of the blast’s depression and hauled away most, but not all, of the Trinitite. It now is illegal to remove any from the national landmark (where radioactivity levels are almost normal).

5) Abandoned in 1942 when the Army took over the area for a bombing and gunnery range, the McDonald Ranch House was vacant until early 1945. Then, it was converted to an assembly point for the A-bomb’s high-explosive and plutonium core; the master bedroom was the scientific “clean room.” Although only about 2 miles directly from the blast, the most significant damage was to the house’s windows. (The barn was severely damage.)

6) The Owl Bar and Café, on the main street in little San Antonio, New Mexico, USA, was busy April 4 during 2015’s first of 2 public tours of the Trinity Site on the Army’s White Sands Missile Range.

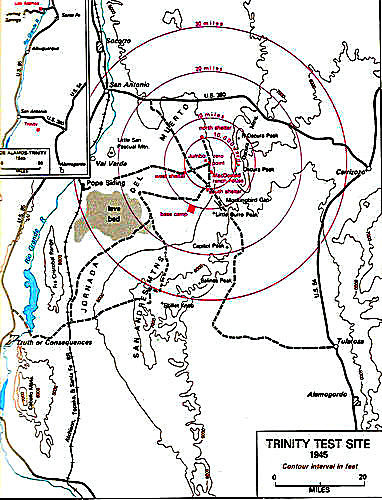

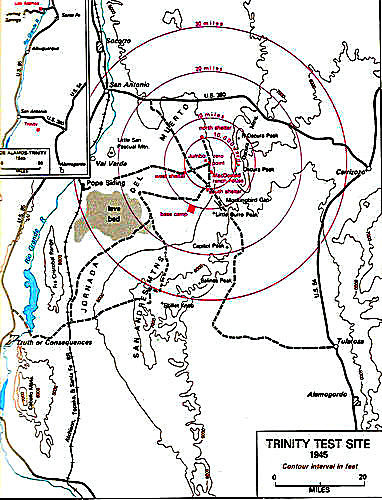

7) An historical map of the Trinity Site area, 1945.

8) April 4, 2015: Writer Kufus beside the obelisk that marks ground zero of the atomic explosion at Trinity Site.

(Copyright: Martin Kufus, 2015)

(Next story: When Pvt. Hendrix kissed the sky)

Email Webmaster with Comments

For More Information...

White Sands Missile Range's Official Trinity Website Link

Interim Report of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Los Alamos Historical Document Retrieval and Assessment (LAHDRA) Project, Appendix N: The Trinity Test—2008 document is highly detailed with photographs, maps, and even graphics of the radioactive-fallout plume.

PDF Link

American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer—the 721-page biography, first published in 2005, won the Pulitzer Prize. It ultimately is a very sad story.

Army public-affairs coverage of Trinity’s April 4 “open house,” in WSMR’s Missile Ranger weekly newspaper:

Link

4) Residue from the atomic test still exists at Trinity Site. 1945’s nuclear fireball melted sand on the ground but also sucked it high into the superheated air and it fell to earth as drops of colored liquid. It coalesced into a new substance: “Trinitite.” Decades ago, Atomic Energy Commission crews filled in much of the blast’s depression and hauled away most, but not all, of the Trinitite. It now is illegal to remove any from the national landmark (where radioactivity levels are almost normal).

4) Residue from the atomic test still exists at Trinity Site. 1945’s nuclear fireball melted sand on the ground but also sucked it high into the superheated air and it fell to earth as drops of colored liquid. It coalesced into a new substance: “Trinitite.” Decades ago, Atomic Energy Commission crews filled in much of the blast’s depression and hauled away most, but not all, of the Trinitite. It now is illegal to remove any from the national landmark (where radioactivity levels are almost normal).