When Private Hendrix kissed the sky

By Martin Kufus

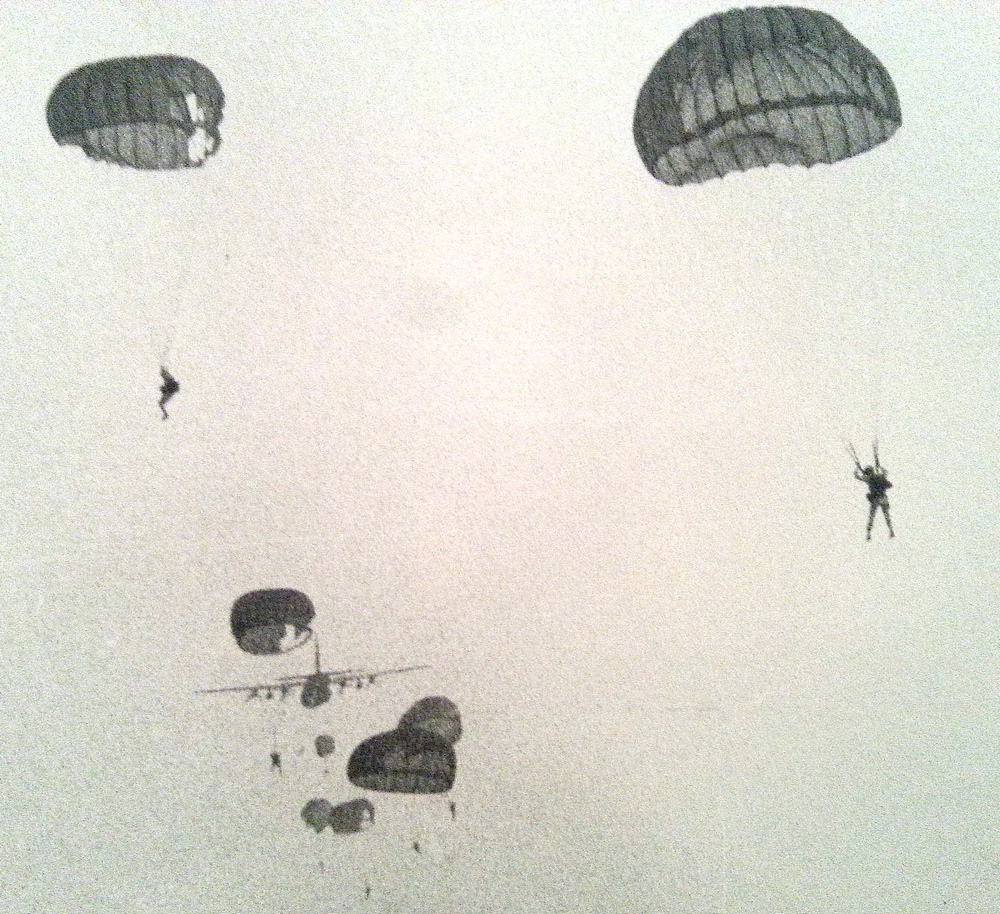

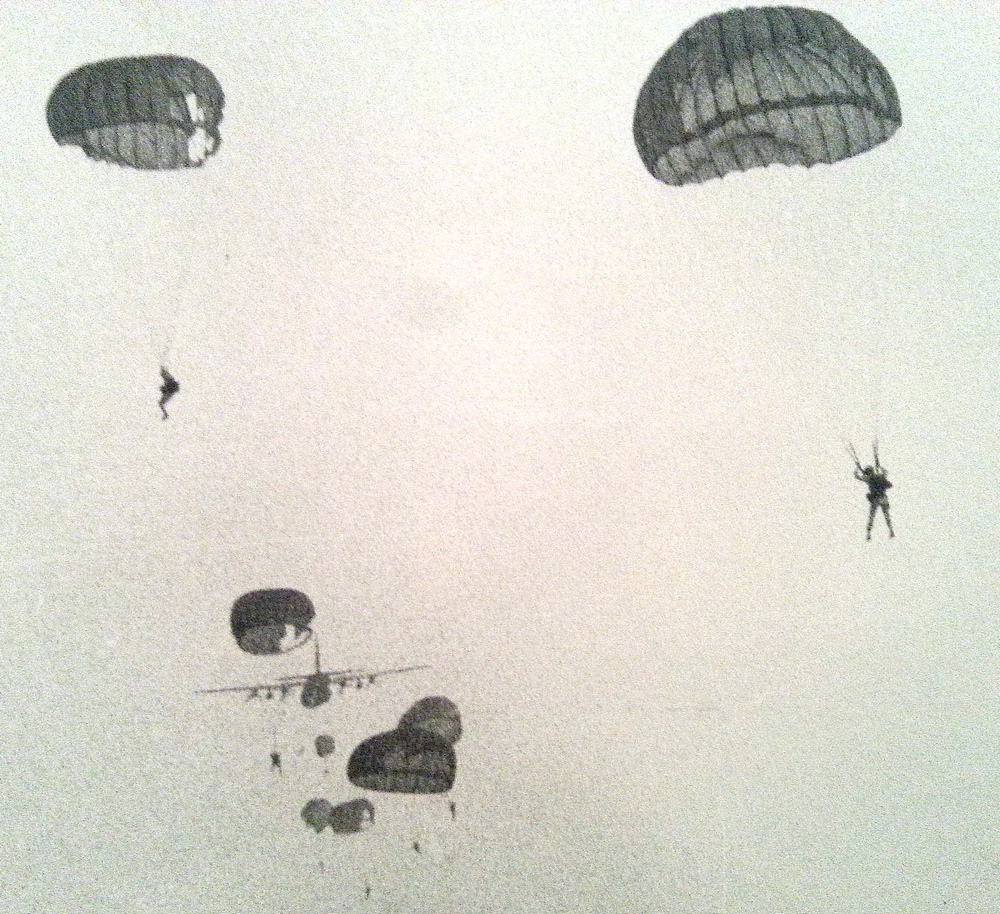

The US Air Force transport aircraft flew a wide circle above the large, parachute-landing (“drop”) zone on Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Crowded in the cargo bay of the 4-engine aircraft was a platoon of Army paratroopers. In the 101st Airborne Division, everybody liked the additional money for “jump pay” but some of the men secretly dreaded the jumps. Others just did it and didn’t think too much about it. Private James Marshall Hendrix, however, loved to parachute.

The US Air Force transport aircraft flew a wide circle above the large, parachute-landing (“drop”) zone on Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Crowded in the cargo bay of the 4-engine aircraft was a platoon of Army paratroopers. In the 101st Airborne Division, everybody liked the additional money for “jump pay” but some of the men secretly dreaded the jumps. Others just did it and didn’t think too much about it. Private James Marshall Hendrix, however, loved to parachute.

The young, black soldier delighted in the other-worldly experience of falling, shaken and engulfed in noise, then floating to Mother Earth. It was one of the few things the 19-year-old paratrooper liked about the Army, which he had joined a year earlier in 1961. Today’s combat-training jump once again would put him out in the sky, on his own.

“Six minutes!”

Sitting in a line of soldiers on seats of nylon webbing, Hendrix looked up, alert. The jumpmaster and assistant jumpmaster—specially trained, senior parachutists—were standing at the rear of the cargo bay, each holding up 6 fingers and looking intently at everybody. (The Air Force crewmen stood back and merely watched.) Jimmy put on his steel helmet and tightened the chin strap. He thought about Betty Jean and what he’d do with her later.

“Betty Jean” was his electric guitar.

The few minutes passed, then it was time. The jumpmaster gave the word, shouting and gesturing; the paratroopers stood up in the narrow aisles. They quickly obeyed the commands: Hook up! Check equipment! Check static lines! Sound off for equipment check!

With flourish, the jumpmaster performed his final duties. He spread his arms and legs, bracing himself inside the portside doorway, and arched his body into the airstream behind the wing. The jumpmaster looked out, all around the aircraft and forward to the approaching drop zone. On the DZ there was no smoke grenade—no red, purple, or yellow haze—signaling “Abort the jump.” Behind him, his assistant stood in the starboard doorway. Satisfied with what they saw, the 2 soldiers came back inside.

Private Hendrix felt subtle motion, a dip in his stomach, as the propeller-driven aircraft descended to about 1,200-feet altitude. He bent his knees slightly and shifted his weight against the slight rolling of the big airplane. The jumpmaster motioned the first group of jumpers to step toward the rear. Their left arms were bent upward, hands clutching yellow static lines whose metal hooks slid noisily along a steel cable. Thirty seconds later, little red lights around the cabin blinked off. Green ones blinked on.

The soldiers did not move; the Army jumpmaster—not the Air Force pilot—had the final decision. The jumpmaster quickly stuck his head outside and looked again, then returned inside. “Go!” he yelled, pointing to the void.

The jumpers rushed forward. Then it was Hendrix’s turn; his adrenaline surged. In one practiced motion, he toed the edge of the opening with his right boot, wrapped his fingers around the sides of the doorway, and leaped.

The roaring turbulence knocked him rearward like a rag doll. Gravity pulled him down, his body bent, legs straight. Chin tucked onto chest and hands around the reserve parachute strapped across his belly, he counted—shouted—the seconds. Then he was jolted as the main ’chute on his back opened. He looked up between the 4 risers at a canopy of olive-green nylon, big and round, no malfunctions. A toothy grin spread across his boyish face.

As he had been trained to do, Hendrix began steering his parachute. He looked below, choosing a clear spot on which to land. Once again, Private Hendrix had kissed the sky.

Jimmy was living with his father in their home city, Seattle, Washington state, when he enlisted into the Army at age 18. He was a good kid, smart, popular with the girls, and good on the guitar, which he played left-handed. He had taken up the instrument a few years earlier after hearing recordings of Muddy Waters’ rhythm-and-blues guitar. A self-taught musician, Jimmy played in some Seattle bands.

In the 1981 book ’Scuse Me While I Kiss the Sky: The Life of Jimi Hendrix, biographer David Henderson wrote that a saxophone player Jimmy knew had gone into the Army and returned, on furlough, as a 101st Airborne paratrooper. “Everyone was really impressed and so was Jimmy,” Henderson wrote.

Jimmy’s father, Al, was surprised when his son told him he wanted to enlist for the “Screaming Eagles,” the famed 101st. A former jazz dancer, Al had been drafted into the Army in World War II and served in the South Pacific. On the other side of the globe, the 101st Airborne’s infantrymen dropped behind German lines in Occupied France just before Allied forces hit the Normandy beaches on D-Day 1944. (In 1968 the Army would change the 101st to a helicopter-assault unit—no more parachutes.)

In 1945 Al Hendrix was discharged. He returned to Seattle and a divorce from Jimmy’s mother, Lucille.

In an interview with Henderson, Al Hendrix recalled a conversation with his son:

He said he wanted to get into the Screaming Eagles and I said, “Oh wow! You going on further than ol’ Dad did.” I remember I told him when I was in Fort Benning, Georgia, we used to watch them guys jump in their practice parachutes. Man, them paratroopers were double-timing … When Jimmy told me that he wanted to be a paratrooper, I said, “Oh, no!”

“Son, you gonna be double-timing your whole time.” He said, “I want to get one of them Screaming Eagles [shoulder patches], Dad.” “Well, that makes me feel real proud,” I said.

After basic training and occupational school, Jimmy attended the Airborne course, “jump school,” at Fort Benning. Like the other students, he quickly lost what little hair was on his head—just like basic training all over again. He walked practically nowhere, outside the barracks: the “Black Hat” cadre made everybody jog. Punishment was in the form of many pushups. But Jimmy was young and slender with wide shoulders, long arms, and wiry muscles. He put up with the hours of ground training wearing parachute harnesses and hanging from cables and also dropping and rolling onto the ground. Finally, in the last week of training, he made his first parachute jump.

After Jimmy settled in at Fort Campbell, he had his father send him his electric guitar. The young soldier’s mind had been stimulated with unusual new sights and sounds. His music would be the outlet for these stimuli. “Fort Campbell had really been the place where he had first made it on his own,” wrote Henderson.

He had dug jumping out of planes. Sometimes he would even take pictures with a camera while jumping. … He had reveled in the sound of the big plane lumbering through the air. … The sound of the door opening was even more enthralling. The rush of air into the cabin, the howling singing of the wind surging in, augmenting the sound of the engine. It had been a true marriage of machine and nature; the sound, the energy. And then falling. …

When he got his guitar from his father he began to experiment with duplicating the sound of heavens. … Like the engines of the plane and the resistance of the air made another unique quality, another unique sound, more than the air, more than the engine, more than a wind—it made a sound that sang. … It was the sound of speeds and heights the human body could not attain itself.

He spent much of his free time playing guitar, experimenting—which eventually got on the nerves of other soldiers living in the barracks. Aloof and increasingly preoccupied with music, Jimmy became the butt of jokes, the target for abuse. His fellow paratroopers thought it was weird that Jimmy began sleeping with the guitar (to protect it from theft).

The young soldier got passes from Fort Campbell and hung out in nearby Nashville, Tennessee, taking in its music and thinking about his future. Jimmy’s opportunity to pursue his musical calling came in June 1962 when he left the Army early as a disciplinary problem (but with an Honorable Discharge).

Jimmy and another ex-paratrooper formed a band and made some money playing rhythm-and-blues shows around Fort Campbell. Jimmy later tried to break into Nashville’s music scene but could not make a living at it. In 1962 he headed back toward Seattle, ending up just to the north in Vancouver, Canada. Jimmy played in local clubs until 1963, when Little Richard and his band passed through Vancouver—taking Jimmy with them. By 1964 Jimmy had played guitar for Sam Cooke, the Isley Brothers, Ike and Tina Turner, and Jackie Wilson.

In 1966 he moved to Britain to record. His first single, “Hey Joe,” hit the British charts in 1967. (By then he had changed the spelling of his first name.) He teamed up with 2 British musicians, Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell, to form the “Jimi Hendrix Experience.” Their first album, “Are You Experienced?” featured the songs “Purple Haze” and “Foxy Lady.” It sold approximately 500,000 copies. Nobody could manipulate an electric guitar and the high-decibel feedback of amplifiers the way Jimi could. He was the original heavy-metal guitarist. He also could take other musicians’ songs and innovate a distinct sound, such as with Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” the Troggs’ “Wild Thing,” and, at Woodstock, his electric-guitar version of the patriotic “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

In 1968 Jimi was deep in the rock-music subculture, his behavior becoming more outrageous and his use of illegal drugs, notably LSD, increasing. He was idolized by his fans, and was a music hero, too, to many American soldiers fighting in Vietnam—especially young black troops. Like other rock musicians, Jimi opposed the Vietnam War. Unlike most of the musicians, though, he knew what it was like to serve in the military.

The Vietnam War raged and American society was in turmoil when Jimi Hendrix departed on the ultimate experience: death.

Early on September 18, 1970, exhausted from hard living and possibly sick with the flu, Jimi took a heavy dose of strong sleeping pills on top of alcohol. He was staying in a friend’s apartment in London, England, and simply wanted to sleep. The chemical mixture was too much for his weakened body. Later, an unconscious Jimi asphyxiated, choking on his vomit. He was 27 years old.

Early on September 18, 1970, exhausted from hard living and possibly sick with the flu, Jimi took a heavy dose of strong sleeping pills on top of alcohol. He was staying in a friend’s apartment in London, England, and simply wanted to sleep. The chemical mixture was too much for his weakened body. Later, an unconscious Jimi asphyxiated, choking on his vomit. He was 27 years old.

In 1985 a large, four-engine Air Force transport jet flew at low altitude above Fort Bragg, North Carolina. It carried Army paratroopers who were practicing a combat-equipment jump. In addition to their parachutes they carried rucksacks, combat gear, and M16 rifles. A 27-year-old sergeant, a Russian linguist in Special Forces, waited to jump. He let his mind fill with the iconic song “Purple Haze” by Jimi Hendrix.

Around the aircraft’s large cargo bay, little green lights blinked on…

Photo: paratrooper Martin Kufus, 1983, in Egypt.

Next story:

Guarding a hazardous-cargo ship against Somali pirates

xxxxxxx

The US Air Force transport aircraft flew a wide circle above the large, parachute-landing (“drop”) zone on Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Crowded in the cargo bay of the 4-engine aircraft was a platoon of Army paratroopers. In the 101st Airborne Division, everybody liked the additional money for “jump pay” but some of the men secretly dreaded the jumps. Others just did it and didn’t think too much about it. Private James Marshall Hendrix, however, loved to parachute.

The US Air Force transport aircraft flew a wide circle above the large, parachute-landing (“drop”) zone on Fort Campbell, Kentucky. Crowded in the cargo bay of the 4-engine aircraft was a platoon of Army paratroopers. In the 101st Airborne Division, everybody liked the additional money for “jump pay” but some of the men secretly dreaded the jumps. Others just did it and didn’t think too much about it. Private James Marshall Hendrix, however, loved to parachute. Early on September 18, 1970, exhausted from hard living and possibly sick with the flu, Jimi took a heavy dose of strong sleeping pills on top of alcohol. He was staying in a friend’s apartment in London, England, and simply wanted to sleep. The chemical mixture was too much for his weakened body. Later, an unconscious Jimi asphyxiated, choking on his vomit. He was 27 years old.

Early on September 18, 1970, exhausted from hard living and possibly sick with the flu, Jimi took a heavy dose of strong sleeping pills on top of alcohol. He was staying in a friend’s apartment in London, England, and simply wanted to sleep. The chemical mixture was too much for his weakened body. Later, an unconscious Jimi asphyxiated, choking on his vomit. He was 27 years old.